Sputnik Sweetheart

Sputnik Sweetheart Dance Dance Dance

Dance Dance Dance The Wind (1) and Up Bird Chronicle (2)

The Wind (1) and Up Bird Chronicle (2) Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman Absolutely on Music: Conversations With Seiji Ozawa

Absolutely on Music: Conversations With Seiji Ozawa Norwegian Wood

Norwegian Wood South of the Border, West of the Sun

South of the Border, West of the Sun Kafka on the Shore

Kafka on the Shore Men Without Women

Men Without Women After Dark

After Dark Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World 1q84

1q84 The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche

Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche Vintage Murakami

Vintage Murakami The Elephant Vanishes: Stories

The Elephant Vanishes: Stories Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage First Person Singular

First Person Singular After the Quake

After the Quake A Wild Sheep Chase

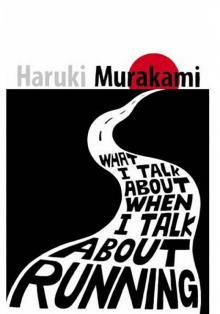

A Wild Sheep Chase What I Talk About When I Talk About Running

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Birthday Girl

Birthday Girl The Elephant Vanishes

The Elephant Vanishes Norwegian Wood (Vintage International)

Norwegian Wood (Vintage International) Wind/Pinball

Wind/Pinball Norwegian Wood Vol 1.

Norwegian Wood Vol 1. Underground

Underground Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage: A novel

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage: A novel Killing Commendatore

Killing Commendatore Absolutely on Music

Absolutely on Music